The 2 Seas, Bahrain

Bahrain – an archipelago of 33 islands [and growing], historically known as Dilmun, stood a fertile agricultural island and important trading route. Bahrain is the sea. Bahrain literally means ‘two seas’. The splendor of the island, with its fresh ground water feeding her lush green landscape was why Bahrain, then Dilmun, was known as the Garden of Eden in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh.

Flamingos painted the horizon orange-pink in the shallow waters of Sitra. The mangroves of Tubli Bay, home to fish, shrimp, and migrating birds, fed off the fresh water run-off from the opulent farms it passed. From Diraz to Ras Rumman [literally pomegranate tip] a stream of water flowed surrounded by palms rich with dates in the hot and humid summers.

The land of a million palm trees and home to several palm species. Whether the Mawaji [مواجي] date, the first the summer season yields, or the Ghurra [غرة], Khalas [خلاص], Kheneizy [خنيزي], Burhi [برحي], Shishi [شيشي] or Khasab Asfoor [خصب عصفور] the last harvest of the season. Bahrain was always known for its cool streaming ground water, its palm trees and its simple, loving people.

Three things take away sadness: water, greenery and a beautiful face

– Regional proverb

Palms lined the sea with their trunks rooted in the earth and the fronds waving to the blue waters. The pearl divers would leave in their Banoosh [بانوش] chanting, “Oh ya maal,” [اوه يا مال] while their women would stand by the shore asking the treacherous sea to bring their loved ones home safely. The seas surrounding Bahrain were as plentiful as the lands, with pearls, but also fish, including Safi [صافي], a local favorite found in the waters surrounding the island, typically eaten with white rice.

Traders came to Bahrain from Persia, India, Yemen, the deserts of Arabia, Oman and Iraq, and with them brought goods, but more importantly, culture, making Bahrain not merely a trading destination, but a pillar for religious and philosophical education with scholars like Shaykh Maitham Al Bahrani, known for his work on the Akhbari school of thought and poetry, Sayed Hashem Al Bahrani, known for his exegesis of the Quran, and Shaykh Abdulla Al Samahiji, from the island of Muharraq – who fled Bahrain upon the Omani invasion of 1717.

Bahrain, the island of a million palm trees. Tylos, as the early Greeks knew it. Awal, as it was known before the appearance of Islam. Or Dilmun, the Epic of Gilgamesh narrates, is where,

The lion kills not, the wolf snatches not the lamb, unknown is the kid devouring dog. [1]

It describes the Garden of Eden, Bahrain, a plentiful land of peace, where the Sumerian King Gilgamesh sought the “Flower of Immortality”.

That is the Bahrain of yesteryear.

Yet today, in post-oil Bahrain, all this is history… stories to tell generations of the malls and branded waterfront lifestyle reclamation projects.

This journey begins on the shores of Damestan\ Dumistan [دمستان], a village on the west coast of mainland Bahrain. Historically, Damestan had been home to fishermen, farmers and scholars, most notably Sheikh Hasan Al Damestani / الشيخ حسن الدمستاني (d. 1759). The people of Damestan occupied this land for centuries and it has been a fixed point in Bahrain’s geography and history. In Damestan, we sought out to tell a story, of the island of Bahrain’s inaccessible coastline, frequenting it with artists, thinkers and passionate urbanists.

However our story was nowhere near as compelling as the tale of the villagers and their loss.

Google Earth 7.1. 2013. Damestan 26°07’16.88″N, 50°28’23.22″W, 13 January 2015. 7 July 2015. Key – 4 pointed star: Damestan beach; 5 pointed star: Abu Rummana Mosque

Damestan, Bahrain

Thirty-five years ago, where we stood by the water displaying the work of young Bahraini artists, was not land; it was sea. If you happened to be in the water back in time looking to the shore, you would see a “jungle of palm trees,” an elderly Damestani recalled with a broken voice. The coastline was “close to the Abu Rummanah Mosque [مسجد أبو رُمّانة]”, around a kilometer away. Once a fishing village by the sea, today we maneuvered walled, private reclaimed land to reach the waters, that defined this place.

Owned. What?

“We say, ‘land belongs to people and the sea belongs to God.’ Yet here, even that is reversed.”

Land ownership is a common practice and business around the world. Yet it is not merely informed by the prospect of a place to occupy and grow, rather land is directly attached to one’s identity. It is the landscape of human development and production, hence the domain of occupation becomes the domain of definition and self-reflection. Guarding land is a sacred human act, as it is seen as guarding one’s self.

In Bahrain, land ownership is one story, however a more compelling story is that of sea ownership.

I vaguely remember from my childhood what our parents and grandparents talk about of the village’s greenery along the sea. Today, it all belongs to them. We feel like we’re being suffocated.

– Young Damestani

The voices of the villagers that spoke of the coast, the sea and the palm groves, much more than the words they chose, bore a deep sense of loss for the right to access the sea and nostalgia for the landscape that had been taken away from them physically, yet still resounded in their collective consciousness. The sea had been blocked away with private reclaimed land, and to the soul of a Damestani, that was torture.

I dream, every so often, of a day while I was young playing with my cousin running through the palm groves by the sea with a cool breeze accompanying us. I would wake up in the middle of the night feeling a deep sense of ease. Oh, those were the days.

Sea ownership has been a mechanism Bahrain’s elite have historically used to form alliances and create wealth. Through elements in the State, they create a parcel in the sea and transfer its ownership from the State to private individuals as a “gift”, creating the unusual situation where somebody owns part of the sea.

They have taken our palms and sea and destroyed it all for their interests. Our sea used to be so plentiful of fish that we had five times the number of fishing areas we have now. Back then, you would have to go and empty your fishing traps every couple of days because they would get full so quickly. But with the reclamation, once a week is more than enough.

Thereon, some “sea owners” would reclaim the sea creating additional waterfront land, which is more valuable than a parcel inland. The owner would sell the reclaimed parcel generating a huge amount of wealth at the devastating social, ecological and economic cost to those whose lives were shaped by that place and whose livelihoods depended on it for sustenance. Extensions of themselves cut and let to whither.

The legality of sea ownership and its reclamation is questionable at best. Article 11 of the constitution of Bahrain states,

All natural wealth and resources are State property. The State shall safeguard them and exploit them properly, while observing the requirements of the security of the State and of the national economy.

In the eyes of the people and the coastal population of Damestan, the sea and the palm beaches are nothing short of a natural resource and an extension of their identity.

Countries like the United Kingdom have everything from the high tide down owned by the crown, held in guardianship and preventing commercialization. In the United States “both the water and the land under the water are owned, are common to all people,” as the 19th century case of Arnold vs. Mundy’s verdict stated. Beaches are protected. The sea belongs to the people. That is the practice worldwide.

@waleedsha3lan, Instagram

الساحل حق عام

The coast is a public right

My Land, My Sea: Right of Access

After years of protests and active pursuit, the villagers were given promises of a beach that would actually be theirs, belonging to the public. Maintaining a real connection to the sea, with amenities including a children’s playgrounds, a boat dock and family sitting areas. A ceremony was held with the Minister of Works, Municipalities, and Urban Planning attending, and a plaque was erected in the event’s memory. Recently, however, the Minister, a different one than the one attended the ceremony years ago, in response to a question by a Bahraini parliamentarian said that the proposed waterfront site,

… would not fulfill the project’s requirements due to problems of private ownership that limit the ability to execute the project as it should. [2]

Ever since, that plaque has disappeared. One villager says,

I think they [in reference to the Ministry] came and took the plaque so that there would be no physical proof of what happened.All the promises, all the statements, all the things you hear are mere talk for the papers. While on the ground, things are only becoming worse. I cannot even get a permit to go fishing in the sea.

Currently, the people of Damestan have no access to the sea except through a 350 meter strip of private land granted as a “gift”. Nobody knows who really owns the land, for land ownership in Bahrain is confidential and such information is not open to the public, yet one thing is known for sure: it is privately owned. The sea overlooking that strip of land is also private property. Looking to one’s left, one finds a walled private property. Looking to the right, one finds the same. Looking behind, one finds another privately owned land and yet another wall. Once this land, too, is developed, the people of Damestan would have no access to the sea.

The sea is their oxygen. They would cease to breathe.

At times we blame our parents and grandparents for not taking a stance when the reclamations and land confiscations started happening. Yet looking back, who knew they would go so far?

Show Me the Numbers

To better understand the extent of land creation and thus wealth creation through sea ownership, it is worth visiting some land related statistics published by Bahrain’s Survey and Land Registration Bureau (SLRB) and the Central Intelligence Organization (CIO).

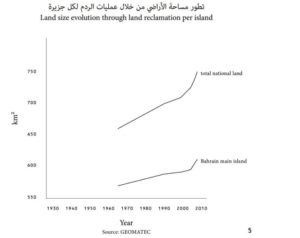

In the year 2000, the land area of Bahrain was 711.85 sq. km., and in the year 2012 the land area of Bahrain was recorded as 770.00 sq. km. That is an increase of more than 8% of the total land area of Bahrain or 58.15 sq. km. in the span of twelve years. Studies conducted in 2010 by “Reclaim”, Bahrain’s Ministry of Culture’s contribution to the Venice Biennale in 2010, showed the area of Bahrain being approximately 660 sq. km. in the mid 1960’s with a steady increase up until the turn of the millennium, with a sharp increase ever since to today’s land mass, an increase that the people of Damestan have suffered from.

Yet the people of Damestan recall the first reclamations at their shores beginning in the early 80’s, approximately ten years after the dissolution of Bahrain’s first National Assembly. Thirty-five years later, what was Damestan’s coastline is now reclaimed land with most plots being private residences or weekend garden homes and a few others being agriculture related businesses, disconnected from the place’s soul.

Now What?

The effect of such land ownership has been devastating to the ecological environment, the local economy, and to the soul of the people. What was once a “shore filled with so many fish that you could catch them by your bare hands,” today is exploited for the benefit of a few whom have no connection to the land nor the sea (and some, not even to Bahrain). The people of Damestan see their identity intrinsically rooted to what is now “private” sea and vanished palm groves, yet, they have not lost hope. They continue to take a stance whether it be through active community work by keeping the shore clean and lively, by anonymous writings calling for self-determination on the private walls that surround the last strip of land they have access to.

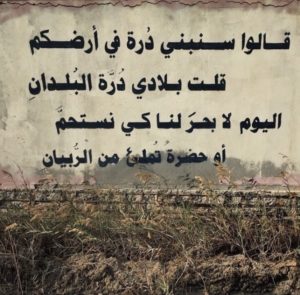

قالوا سنبني درة في أرضكم

قلت بلادي درة البلدان

اليوم لا بحر لنا كي نستحم

أو حضرة تملئ من الربيان

They said we shall build a pearl in your land,

I said my land is the pearl of all lands.

Today we have no sea to swim in,

Or sea to catch any shrimp in.

Bahrain, Damestan

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the king finally gets the “Flower of Immortality” from the bottom of the sea. Gilgamesh does not immediately eat it; rather stops to bathe. In the meanwhile, a serpent steals it from him and takes his opportunity to immortality from him. As I recalled Gilgamesh, a Damestani fisherman points to parts of the sea and coastline where he is no longer allowed to sail past, let alone own sea. And then he points to an island off the coast. And looks at me with a smirk…

We, in Damestan, welcome others. We want everybody to enjoy the beach and the sea that we and our forefathers enjoyed. It is not just ours. It is everybody’s.

The sea had a stillness to it that day. I looked to the horizon, where the sea met the sky thinking to myself, what is it that these people have lost? It is not merely land or sea. It is not simply fish and trees. No. They have lost control. They have lost themselves. What yesterday simply was, today is non-existent. They feel trapped between these walls. The walls are violent, the land is taken, and the sea is inaccessible. One can only look at a single direction at this point, to the sky… for now.

Gradually, I realized that this is not the story of Damestan and its sea rather the story of the darkness of oil taking over the clarity of water. This is not the story of a village in Bahrain rather the story of Bahrain in a village… This is the story of two seas.

References:

[1] Conklin, Edward. “Historical Influences.” Getting Back into the Garden of Eden. Lanham, MD: U of America, 1998. 10. Print.

[2] “خلف: الموقع السابق لساحل دمستان لا يلبي احتياجات المشروع.” صحيفة الوسط البحرينية[Manama] 14 Feb. 2015, 4543rd ed.: n. pag. Print.

No comments.